The Essentials of Go

by John H Paquette

Copyright © 2005 John H Paquette

Revised 2025

All Rights Reserved

Introduction

Go is an ancient game, rich in history, tradition, and subtle strategy. I will describe none of it here. Instead, I'll describe the game as if it were invented yesterday. I aim to convey only the essentials of Go—its object and rules—separate from its strategic and cultural aspects. Many primers discuss strategy or tactics (or even history and etiquette) while explaining the rules. My goal is to keep the horse before the cart—to separate the rules from the rest—because they make, and have made, the other aspects of the game possible. After you read the following, you will know how to play the game, but you won't know anything about how to play it well. You will then be ready to learn the strategy of Go.Overview

In the game of Go, two players take turns placing stones on a board. One player plays black stones; the other, white. Each stone you play affects where your opponent can play and may cause some of his stones to be captured (removed from the board). The object of Go is to keep your opponent's stones off the board. Your score is the number of points on the board where your stones make it impossible for your opponent to play.1 At the end of the game, the player with the higher score wins.Equipment

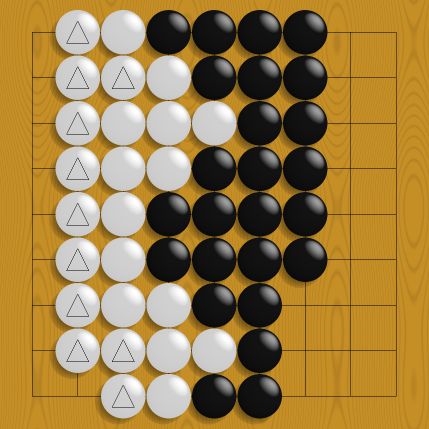

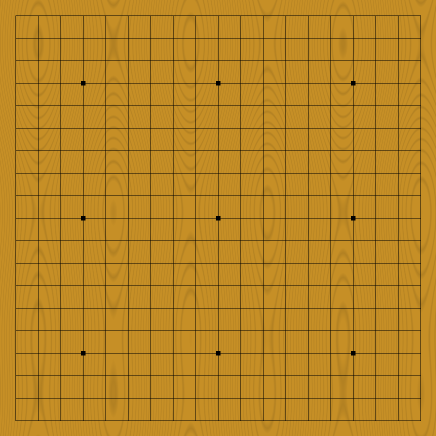

The standard Go board is light-colored, made of wood, and approximately square,2 eighteen inches on a side, with a grid of evenly spaced crossing black lines on it. There are nineteen horizontal lines and nineteen vertical lines. The vertical lines end at the outermost horizontal lines, and vice versa. You can find smaller boards (nine by nine lines, thirteen by thirteen lines) for learning and playing games that take less time. The rules of the game don't depend on the size of the board.

A Go board

Go stones

Basics

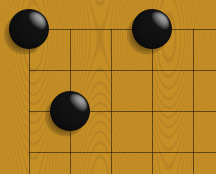

The board begins without any stones on it. The places on the board where the lines intersect, including the corners and the T-shaped intersections along the edges, are called points. Stones are played on the points, not on the squares.

Stones on the points

- doing nothing (passing)

- placing one of your stones on one of the empty points and then, if possible, capturing some of your opponent's stones.

Connection

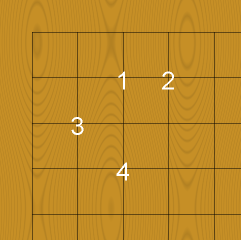

Two points are neighbors if they are adjacent and in the same row or column. If they are diagonally oriented, they are not neighbors. Neighbors are also called neighboring points.

Points 1 and 2 are neighbors. Points 3 and 4 are not.

- they touch,

- each of the two is connected to a single third stone.

The white

stones are all connected. The black stones are not.

Strings

A string is:- an entire group of connected stones,

- a single, unconnected stone.

Three white strings and two black

strings

Liberties

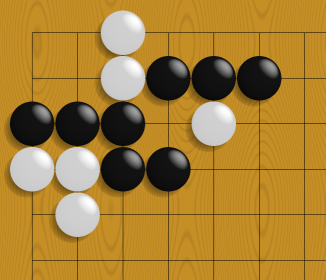

A liberty is an empty point that neighbors a string. A liberty is a way a string might grow. A string's liberties are all its empty neighbors, including those surrounded by the string. Sometimes we speak of a stone's liberties. These are just the liberties of the string to which the stone belongs. The stone itself doesn't need empty neighbors to have liberties—it just has to be connected to one or more stones with empty neighbors.

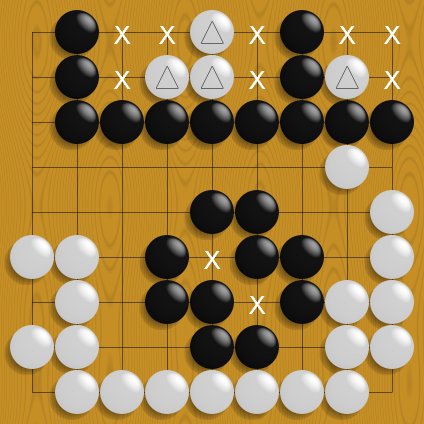

The white string's liberties are marked with X.

The Fundamental Rule of Go

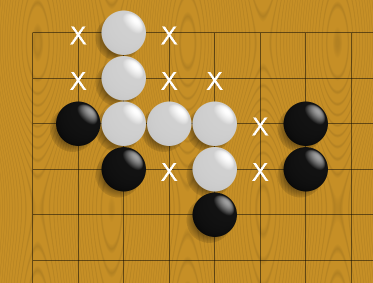

Strings without liberties cannot stay on the board. When a string has no more liberties, all of its stones are captured, and returned to their owner's bowl.3 Each string must be captured as a whole; capturing only part of a string is not allowed. To capture one of your opponent's strings, you play a stone on its last liberty. A single stone can capture more than one string. When you play your stone, look around it, and remove all the strings it captures.

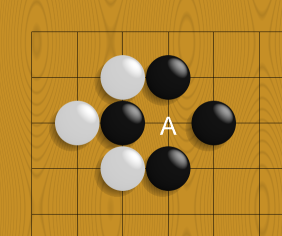

White can capture three strings by playing at A.

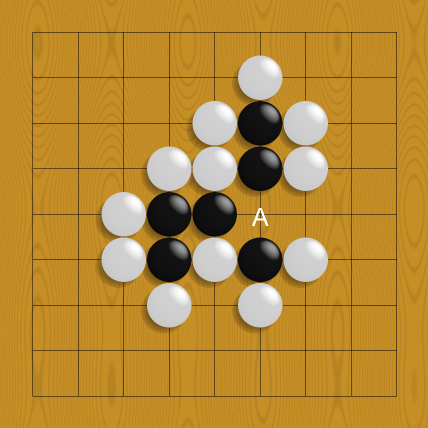

The Rule Against Self-Capture

You cannot place a stone where its string would have no liberties unless doing so captures an opposing string. Capturing creates liberties for the new stone, allowing it to remain on the board.

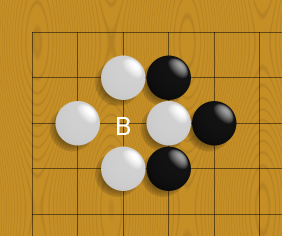

Black cannot play at A but can play at B because it captures the marked string.

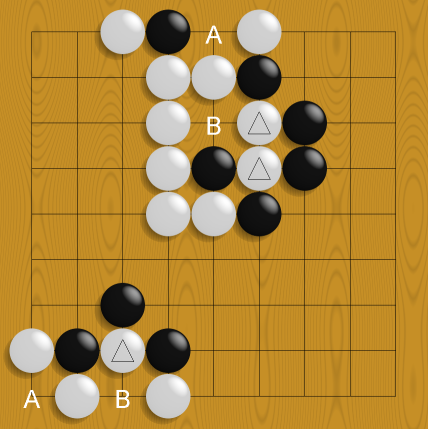

The Rule Against Repetitive Play

You cannot make a move that would repeat a prior board position (with the same player to play). This rule forces the game to progress, rather than stall indefinitely.

After White captures at A, Black cannot capture at B without first playing elsewhere.

Scoring

Your score is the number of points on which your stones make it impossible for your opponent to play. This includes two kinds of points:- those occupied by your stones,

- those empty points where the Rule Against Self-Capture prevents your opponent from playing.

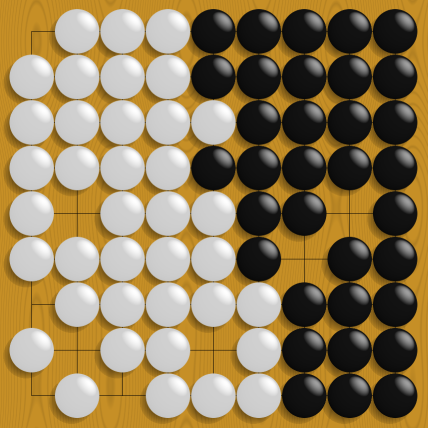

White scores 45 points. Black scores 36 points.

Improving The Game

Playing Go as described above, you'll encounter some tedium. This can be eliminated through some refinements which do not change the basic nature of the game. To understand these refinements, you should play several games without them. To minimize the tedium, you should do it on a small (nine by nine) board, with a full set of stones.Refinement #1: Territory

From playing, you'll notice that each stone on the board ultimately gets captured or becomes invulnerable to capture. At any time during the game, the stones on the board can be classified into three types:- Those that won't ever be captured.

- Those that can't be saved from capture.

- Those whose outcome is uncertain.

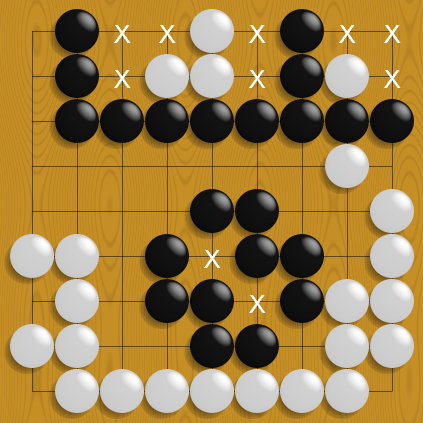

Black's territory is marked with X.

- Your score is the number of points occupied by your stones, plus the number of points in your territory.

- It is always legal (though perhaps foolish) for you to play on any point in your territory.

- If an empty area is between invulnerable stones of both colors, it is no-one's territory.

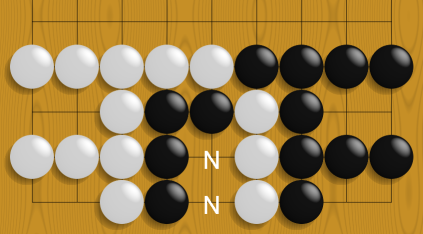

The points marked with N are no-one's territory.

Refinement #2: Doomed Stones

A doomed stone is a stone on the board that can't be saved from eventual capture. Doomed stones have liberties, but these liberties are within the opponent's territory. This is what makes it futile to attempt to keep a doomed stone on the board. Playing a stone (into your opponent's territory) to try to save a doomed stone only dooms another stone.

Doomed stones are marked. Black's territory is marked with X.

- Your score is the number of points occupied by your invulnerable stones, plus the number of points in your territory, plus the number of doomed stones your opponent has on the board.

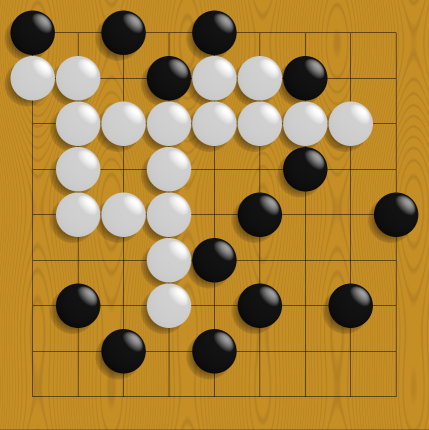

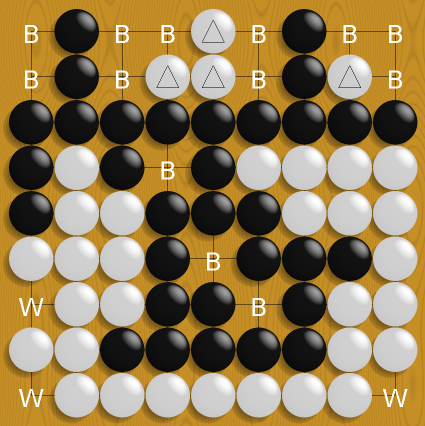

Black's territory is marked with B; White's territory is marked with W. Black scores 49 points (32 invulnerable stones + 13 territory + 4 of White's doomed stones). White scores 32 points (29 invulnerable stones + 3 territory).

Refinement #3: Score Equals Territory Minus Captives

So far, we've computed the score of each player by adding his territory (after removing all doomed stones) to the number of his stones on the board. Note, though, that for each player:- Stones on board = stones played - stones lost.

- Territory + stones played - stones lost.

- Territory - stones lost.

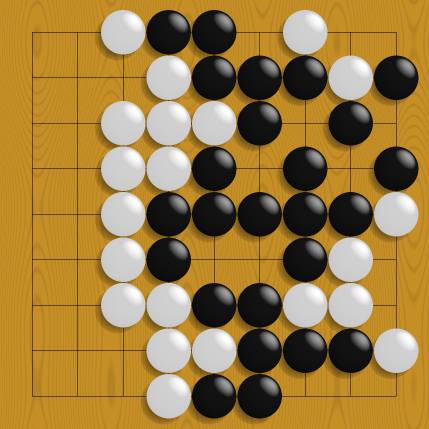

The end of a game. Black has captured 4 white stones (not shown).

The 4 captured white stones are placed into White's territory (marked). White's doomed stones are marked.

White's doomed stones are moved into his territory. White's final score is 10 points.

Black's territory is rearranged for easy counting. Black's final score is 21 points.

Handicaps

If one player is much stronger than the other, the game can be equalized by handicapping the stronger player. This is done by starting the game in two possible ways:- Allowing the weaker player (playing Black) to make two or more moves before the stronger player (White) makes his first move.

- Doing the same thing, but assigning these initial moves to specific points on the board, called star points, designated by dots.

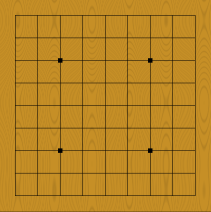

The star points on a 19 by 19 board, a 13 by 13 board, and a 9 by 9 board.

- 2: in opposite corners

- 3: on a diagonal

- 4: on the corners

- 5: like 4, plus one in the center

- 6: like 4, plus two on opposite sides

- 7: like 6, plus the center

- 8: on all star points but the center one

- 9: on all star points

- 2: on a diagonal

- 3: one corner empty

- 4: on all star points

Conclusion

I've described only the essence of Go—its object and rules—and some refinements that remove tedium from the game. The refinements are not mine. They are part of the tradition of Go. They are so compelling that experienced players never play without them. The rules of Go are pretty simple. What's difficult is identifying territory. Doing so requires knowing what kinds of stone configurations are invulnerable, and knowing how much board area is needed to create invulnerable configurations when your opponent is trying to prevent you from doing so. Identifying territory is an impossible task for a beginner.5 But Go has long been defined as a game whose object is to surround territory. This is unfortunate for beginners. They cannot know what territory is until they learn to play the game, and they cannot play the game without a notion of its object. Surround territory is the object they are usually given. In writing this article I wanted to define the object of Go so that beginners could understand it. The result was to introduce the notion of territory later, as a refinement to the fundamental game. I hope you've enjoyed learning about Go, and I hope you go on to enjoy playing the game as much as I do.Footnotes

- If you are an experienced Go player and this definition of the score isn't what you are familiar with, please bear with me. Refinements #1 and #2 will address your concerns.

- Traditionally, the board is not square; it is slightly taller than it is wide—the horizontal lines are slightly farther apart than the vertical lines. This makes the board look more square from each player's point of view.

- To experienced players: I'm describing Chinese scoring first. Japanese scoring is covered in refinement #3.

- The outcome is affected only as much as one player plays more stones than the other. For the best score you should pass rather than play stones into either player's territory. Playing into your territory will only make it smaller, and playing into your opponent's territory will only doom your stone. In either case, your score suffers.

- And so I explicitly place it beyond the scope of this article.